Introduction

As we all know, the field of American studies is multi-disciplinary in nature. This requires the study of various fields, drawing from concepts and ideas from different aspects of culture, be it film, music or dance. What makes studying food any different? Food is one of the only elements of culture that literally become part of the consumer. Food is also one of the basic needs of human beings. When we study dance and song, we are studying self-actualization, the highest tier of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. By studying food, we are essentially going back to the basics of human existence since food is so intrinsically tied to our everyday lives. I have found that, in the course of my research, studying food was like walking on a winding path. Meandering through the history of sushi, I have discovered nuggets of American culture around every bend. It is truly astounding how the study of Japanese cuisine can shed light on American society at points in history. It is precisely this that makes American studies so intriguing.

In this essay, I start by understanding the origins of sushi in Japan, before understanding what led to the sushi’s first contact with America and subsequently, the reasons for its proliferation of popularity in the 60s, 70s, 80s and 90s. I will then touch on how sushi has adapted and assimilated for the American palate. Throughout the essay, I will touch on the key concepts of race, culture, class and authenticity.

History of Sushi

The Japanese have exported countless of great products to the world over the years. These products range across a diverse range of sectors, including Sony entertainment, Canon and Nikon cameras, Toyota and Honda automobiles, Seiko and Orient watches, the Nintendo PlayStation, to name a few. Amongst these famous exports, perhaps the most well-known and remarkable is the rise of sushi. Sushi first originated as a way to preserve fish in rice, approximately 2000 years ago. Contemporary sushi, only came about in the 8th century it’s development into a ‘fast food’ (as opposed to sushi from the lengthy fermentation process) came only during the 19th century in today’s Tokyo.

CC image courtesy of Jeremy Keith on Flickr

CC image courtesy of by Su-Lin on Flickr

Sushi on American Shores

To understand the roots of sushi in America, one must look to the mid 1800s, where the first Japanese immigrants set foot on American soil. Significant volume of immigration was due to social and political liberation in Japan resulting from the 1868 Meiji Restoration. With the Chinese Exclusion act of 1882, the Japanese were particularly sought after to replace the Chinese workers. This led to the first official intake of Japanese migrants in Honolulu, Hawaii.

By hawaiihistory.org, via Wikimedia Commons

The first modern sushi shop, however, was not set up in Hawaii, but rather, in Los Angeles. In 1966, Kawafuku opened its doors in LA’s Little Tokyo. Noritoshi Kanai, a general manager of a Japanese import business in LA, was the owner of Kawafuku. Kanai wanted to spread Japanese cuisine in America and alongside sushi chef Shigeo Saito, they ran a sushi bar on the second floor of the restaurant while serving more familiar Japanese dishes like tempura and teriyaki downstairs.

via pbagalleries.com

Kawafuku could not have opened at a better time in America. The counterculture movement dominated the 1960s, where mainstream thinking on a host of different issues were experiencing change. In music, the rock-and-roll movement of the 1950s fizzled out, while music inspired by psychedelic drugs like LSD lighted up the seen. Jimi Hendrix’s take on the electric guitar usurped Chuck Berry’s outdated style. The same counterculture movement permeated film and fashion. It is no surprise, therefore, that the tornado of change swept through the food scene as well. Attitudes of openness lent themselves to sushi and Kawafuku was a hit with Japanese businessmen and they subsequently introduced the joint to their American business partners. As the popularity of Japanese cuisine grew, word got out to chefs in Japan. In Japan, to be an itamae (sushi chef), one must go through years of strict on-the job training. Sushi-making was considered an art form, justifying the high standards of Japanese chefs. Young Japanese chefs grew disillusioned with the rigorous culture of sushi making back home and the promise of wealth in America was the perfect storm for the rise of sushi in 1970s.

Sushi Rides the Wave of Culture

By the 1970s, sushi bars began to pop up outside of Little Tokyo in surrounding areas of LA. It was not Kawafuku, however, that popularized sushi in America, but a restaurant named Osho. Osho’s clientele consisted of the rich and famous of Hollywood, including Yul Brynner, most famous for his role as King Mongkut in the King and I. Powered by the endorsement of Hollywood celebrities, sushi met with an accompanying tailwind as Americans were encouraged to eat more fish to live a healthier lifestyle. Reports originating from 1977 suggested that fatty, high cholesterol foods should not form more than 30 per cent of daily food intake in order to reduce the risk of heart disease. The heightened awareness to the merits of eating healthy was a boon for Japanese cuisine. In sushi, Americans found a healthy alternative to the meat heavy diet they were used to. The sushi fad in the 1970s was particularly interesting as it developed into a food associated with class and educational standing. This was perhaps best represented when the elite Havard Club in New York City opened a sushi bar. The opening of the sushi bar was met with equal grandiose when the New York Times plastered the announcement on it’s front page. The aesthetical appeal of minimalistic Japanese design and the appeal of aforementioned trend towards healthy foods like rice, fish and vegetables transformed Japanese food from an exotic ethnic cuisine to a sophisticated, exotic food.

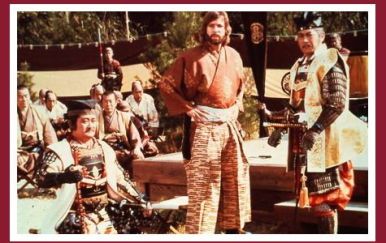

James Clavell’s novel turned miniseries, Shogun, first aired in 1980. The storyline loosely follows the adventures of English pilot, John Blackthorne and his adventures in early 17th century feudal Japan. Interestingly, Shogun was filmed entirely in Japan and Japanese characters were played by Japanese actors. This authenticity was in stark contrast compared to previous films where Asian characters were largely played by white actors in Yellowface. For example, in 1935, Anna May Wong, a Chinese-American star was considered for a role in The Good Earth. The role went to Luise Rainer instead. The producers of Shogun valued authenticity down to the intricate details on Japanese costumes and was rewarded when the show rocketed to fame. It held the second highest average rating in television history and almost a third of all television households watched the series. This reignited a curiosity and openness to Japanese cruisine in America and a new generation of ‘Japanophiles’ were born. Cultural shifts in America throughout the 60s, 70s and 80s all seemed to contributed one way or another to the popularization of sushi.

via richardchamberlain.com

The B Side of Sushi in America

At least that’s how the history of sushi is largely understood in America. One has to wonder, however, that it really took approximately 100 years since the Japanese stepped on American soil for a Japanese restaurant to pop up. An issue of Harper’s Weekly, a newspaper in New York City, described a Japanese restaurant as early as in 1889. Interestingly, Japanese restaurants were popular amongst workmen for being ‘ten-cent restaurants’ and these restaurants drove American restaurants out of business. It is interesting to see the restaurant scene in America 200 years ago as a microcosm of modern America, under the adverse effects of globalization. By 1900, concentrations of Japanese immigrants formed ‘Japantowns’, first in San Francisco and by 1909, there were 232 Japanese-owned restaurants that served Japanese cuisine across America. Adding to that, home design magazines started to display Japanese tea-house designs and Japanese-themed social events started to emerge. It can be said that the first generation of ‘Japanophiles’ in America were developing at the turn of the 18th century. It seems that long before the arrival of Shogun, Americans have already developed a certain sense of fascination with Japanese culture and food. However, all this ended when fears of a yellow peril morphed into anti-Japanese nativism movements, directly leading to the Gentlemen’s Agreement between Japan and USA in 1907. This ended the immigration of Japanese men. In California, the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League was established and they complained to school boards to segregate Japanese children and eventually succeeded. The final nail to the coffin was the Immigration Act of 1924, which limited the number of immigrants and reduced Japanese migration to a trickle. With that, the number of Japanese restaurants dwindled and sushi’s popularity followed a similar trajectory.

Sushi for the Masses

As sushi grew in popularity, there was an ever pressing need for chefs to adapt to the American palate. The two main types of traditional sushi were makizushi (rolled sushi) and nigiri sushi (hand pressed sushi).

By Wikimedia Israel via Wikimedia Commons

By bluewaikiki.com (originally posted to Flickr as Salmon Nigiri Sushi) via Wikimedia Commons

Traditionally, makizushi would consist of ingredients and rice wrapped with a layer of nori (seaweed). After time, chefs realized that Americans found the chewy texture of the seaweed unappetizing and peeled it off before consumption. The American palate also found the combination of raw fish and rice too much to swallow. Alas, enter the uramaki roll. The uramaki roll was an adaptation to the makizushi, with the seaweed hidden inside the rice. The California roll is a prime example of the uramaki roll with imitation crab, cucumber and avocado. The California roll was the first instance of variation of sushi in America. The rainbow roll, spider roll and even the ‘Rock and roll’, followed shortly after. Interestingly, it seemed like American attitudes of innovation and creativity had seeped into Japanese cuisine. Sushi simply provided the canvas for Japanese American chefs to color.

By Mk2010 (Own work) via Wikimedia Commons

CC image courtesy of Michelle Lee on Flickr

The 1990s saw Sushi’s transformation from a sophisticated, upscale and exotic food into an affordable and accessible fast food. In a sense, sushi went through an era of McDonaldization in America. George Ritzer’s book, The McDonaldization of Society, states the four components of McDonaldization, namely efficiency, calculability, predictability and control. Supermarket sushi first appeared in 1995 at the Rockville Fresh Fields store in Washington. Sushi was expensive and difficult to make, but Fresh Fields got around it by contracting a mass supplier of sushi that supplied sushi bars country-wide. The benefits of economies of scale were threefold. First, sushi would be made available to the public for a more affordable price. This meant that sushi was now accessible to the middle class. This phenomenon was the catalyst for the spread of the popularity. Sushi no longer existed as an exclusive food for businessmen and for the cosmopolitan upper class. Sushi was now affordable for the masses. Secondly, the standard of sushi could be controlled and monitored. As aforementioned, consuming raw seafood was one of tougher hurdles for Americans to cross. This reluctance was not merely rooted in a psychological barrier but there were real risks of foodborne illnesses like Salmonella and Vibrio. The quality control from suppliers assured the American public of sushi’s safety. However, even as recent as 2015, salmonella cases have been linked supermarket sushi. Lastly, the consumption of sushi became more convenient. Traditionally, consuming sushi involved a fair amount of etiquette. The nuances of Japanese dining reflect the politeness and formality ingrained in their culture. Eating at a Japanese restaurant was an experience in and of itself. With the arrival of supermarket sushi, sushi became a convenient meal. By the end of the 20th century, sushi was well and truly ubiquitous across America.

Questioning Sushi’s Authenticity

Sushi’s progress in America came full circle when restaurants in Tokyo started serving American sushi. These restaurants leverage on the image of American sushi being healthy, trendy and novel. Sushi was once a pure and sacred tradition in Japanese cuisine. The desecration of sushi in America was welcomed by some chefs in Japan. Americanisation of sushi was perceived as a natural product of globalisation, borne out of the creativity of foreign chefs. Perhaps this was easier to swallow for the old masters of sushi, instead of seeing it as an act of blasphemy. Nevertheless, there has been pushback from Japanese chefs on the authenticity of Japanese sushi and retaining the art of sushi. It is suffice to say, therefore, that the imprint that America left on sushi is permanent and undeniable.

Conclusion

The story of sushi in America is a story of race, popular culture, class and authenticity. First, this study of sushi reaffirms the power and usefulness behind studying something as specific as sushi to see America in a different lens through different time periods. Secondly, it is becoming clearer to me that everything in life happens in cycles. There are cycles in the economy, in the weather, in our nations’ demographics and even in sushi. It can be noted that early on, America’s feared the yellow peril, that the Japanese, Koreans and Chinese would distort society such that it becomes less ‘American’. Now, Japanese chefs fear that America’s influence of will distort Japanese cuisine such that it becomes less ‘Japanese’. This highlights the importance of American studies and the study of history in general. In the words of Winston Churchill, ‘The farther you look back, the farther forward you are likely to see.”

Bibliography

Hsin-I Feng, C. (2012). The Tale of Sushi: History and Regulations. Comprehensive Reviews In Food Science & Food Safety, 11(2), 205. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00180.x

Theodore C. Bestor (2000). How Sushi Went Global, Foreign Policy

Ole G. Mouritsen (2009), Sushi: Food for the eye, the body and the soul

Laurel Randolph (2015). How Sushi Became an American Institution. Retrieved from https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2015/04/how-sushi-became-an-american-institution.html

Laurie Tarkan (2015) Here’s what you need to know about sushi salmonella outbreak. Retrieved from http://fortune.com/2015/07/23/sushi-salmonella-outbreak/

Walter Nicholls (1998) Supermarket Sushi. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/food/1998/04/29/supermarket-sushi/a0811d12-99b1-40ac-b5aa-c4e8b18a0602/

D Miller (2015) The Great Sushi Craze of 1905, Part 1. Retrieved from http://eccentricculinary.com/the-great-sushi-craze-of-1905-part-1/